Project Description

I ended last week’s UK Black History blog with a little profile of Johnny Smythe, who fought in World War Two and went on to become the senior officer aboard the Windrush – which leads me on to this week’s topic.

I recognise that my perspective may have its limitations, so in writing these blogs I’ll be drawing upon reliable sources from the internet, and I’ll include links to articles (click on the blue text where it appears) so that you can read more. If you think I’ve missed something important, or got something wrong, please do comment and let’s open up the conversation to all.

Our schedule is inspired by the suggestions made by colleagues in the recent survey we completed on BHM, and will cover:

- UK black history – from Ancient Britain to the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- UK black history – World War I and World War II

- UK black history – the Windrush generation

- Prominent people in UK black history

If you have articles or information you think colleagues will find interesting, please do share them with us by commenting on these blogs.

You can find out more about the Windrush scandal by watching ‘The Unwanted: The Secret Windrush Files’, a David Olusoga documentary on the iPlayer.

The Windrush generation

During World War Two, many thousands of Caribbean workers had contributed to the war effort either as volunteers in the armed forces or technicians, and while some remained, the majority were de-mobbed and returned to the colonies. After the war ended in May 1945, more than three thousand Caribbean men decided to remain in Britain.

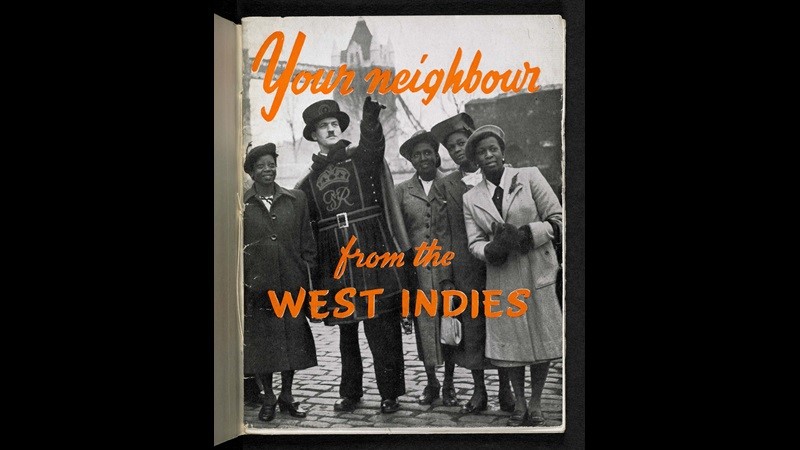

Following World War Two, there was a serious shortage of labour in Britain. To help rebuild the economy, an estimated 1.3 million workers were needed. The British Nationality Act 1948 allowed those from Jamaica and Barbados, and others living in Commonwealth counties, full rights of entry and settlement in Britain. The British Government invited and actively encouraged “fine young West Indians” to come to the UK to take up the job vacancies that weren’t being filled, and many took up the invitation to work as nurses, midwifes, ancillary workers, cleaners, cooks, and porters, as well as factory labourers or employed in the bus, underground, and rail services. Industries like British Rail and the newly-created National Health Service heavily recruited from the Caribbean – others, such as the Metropolitan Police, rejected applicants because of their ethnicity.

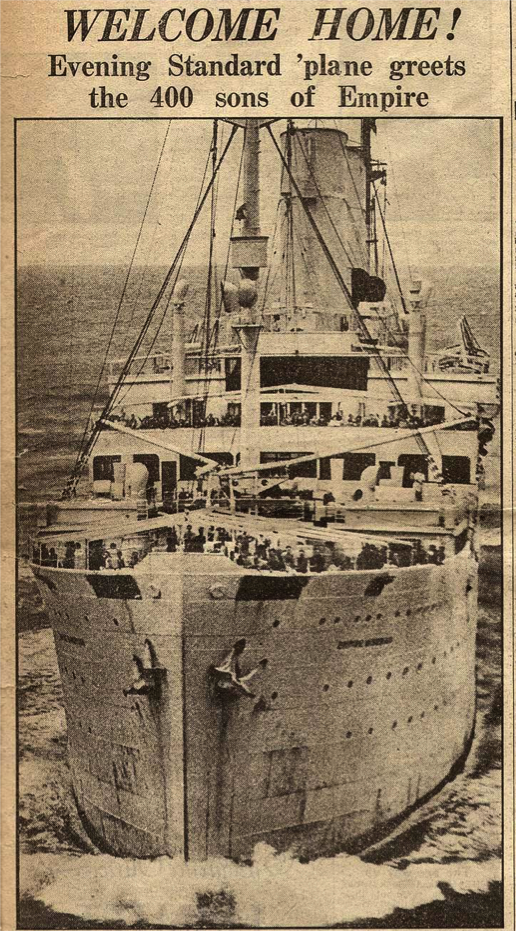

The HMT Empire Windrush was not the first passenger liner to bring people seeking work from the Caribbean to Britain (it followed the Almanzora and the Ormonde), but it is the most famous. The Empire Windrush was originally the MV Monte Rosa, a passenger liner and cruise ship launched in Germany in 1930 that was seized by the Nazi regime and used to transport troops during the war. She was captured by the British at the end of the war and renamed the Empire Windrush. In 1948, she happened to stop over at Kingston, Jamaica, to pick up some British servicemen. Since the ship was not full, passage was offered to Britain for £28 if you travelled in the uncomfortable open berths of the “troop deck”. Around 500 men, women, and children from the Caribbean decided to make the 8,000 mile journey.

People took passage on the Empire Windrush for many reasons. Some were seeking employment in Britain, and others hoped to rejoin the Army or Royal Air Force, while many simply had deep curiosity about the “mother country”.

The ship docked on the Thames at Tilbury on 22 June 1948. Eventually over 500,000 Commonwealth citizens would go on to settle in Britain between 1948 and 1971, and are now referred to the ‘Windrush generation’.

Lord Kitchener (Aldwyn Roberts – above), the innovative ‘grandmaster of calypso’ from Trinidad, travelled on board the Windrush. He had become popular with US troops based on Trinidad during the war, and is known, among other things, for writing the song Jump in the Line. Following his move to the UK he was a regular performer on BBC radio, and he built a large following amongst West Indian migrants in the UK throughout the 1950s. Pathé news captured his arrival on the Empire Windrush when he performed the specially-written song ‘London is the Place for Me’ – the Windrush section of the report starts at 0:45:

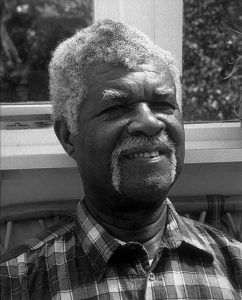

Sam King (MBE) (left) was a Jamaican-British campaigner who first came to England in the RAF during World War Two, and returned on the Empire Windrush. He was heavily involved in London’s West Indian community, helped to set up the 1959 Caribbean Carnival in Notting Hill, founded the West Indian Gazette as the first British newspaper written specifically for a black readership, and became the first black mayor of Southwark.

(left) was a Jamaican-British campaigner who first came to England in the RAF during World War Two, and returned on the Empire Windrush. He was heavily involved in London’s West Indian community, helped to set up the 1959 Caribbean Carnival in Notting Hill, founded the West Indian Gazette as the first British newspaper written specifically for a black readership, and became the first black mayor of Southwark.

The impact of immigration

Many passengers on the Empire Windrush arrived with nowhere to live, and the lack of housing in London following World War Two meant that temporary accommodation was in short supply. The government temporarily housed 236 Windrush passengers without accommodation in Clapham South deep shelter, an air-raid shelter 15 storeys underground. For six shillings and sixpence a week they got food and shelter in the tunnels underneath the Tube station, which had been fitted with bunk beds and washing facilities when they were used as civilian shelters during the war. Within four weeks of arriving, all the Windrush migrants had secured jobs and moved out of the site – one of the biggest employers was London Transport. Many workers eventually settled in nearby Brixton, the site of the nearest labour exchange, beginning the area’s association with Caribbean culture.

Despite having equal rights to British citizenship, new arrivals from the Commonwealth faced prejudice and abuse. Eleven members of Parliament wrote to Prime Minister Clement Attlee after the Windrush’s arrival, complaining about “coloured” immigration. Afro-Caribbean Londoners were sometimes denied employment, housing, and were turned away from churches, pubs, and dancehalls.

Housing in London was in short supply following the bombing during the Blitz, and some Caribbean arrivals faced hostility for “taking” homes, or racism from Londoners who didn’t want to live near Black people. Predatory landlords charged Commonwealth citizens as much as double the rent of white residents in Notting Hill, and crammed them into slum-like conditions.

The number of people living in Britain who were born in the West Indies grew from about 15,000 in 1951 to 172,000 in 1961. Due to a perceived “heavy influx of immigrants”, the British government created the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962, barring the future right of entry previously enjoyed by citizens of the Commonwealth, which many considered a direct bar on Black people.

Racism erupted into violence in Notting Hill in 1958, when gangs of Teddy Boys roamed the streets attacking Black men, and murdering one – Kelso Cochrane from Antigua. A Caribbean Carnival was held to try and improve race relations in 1959, later becoming the Notting Hill Carnival.

Notting Hill and Dale, which had been declining parts of the inner city, were gradually revitalised during the 1960s and 1970s. Some Afro-Caribbean new arrivals opened cafés and clubs, and Notting Hill gained a reputation as a bohemian area, attracting a young, trendy crowd of White as well as Black people. Across London and Britain, the Windrush generation helped to rebuild the country from the devastation of the Second World War.

This Windrush generation would start up newspapers and introduce new musical tastes – ska, reggae, calypso, jazz, funk, rock, and pop – and bring new styles of dress, colour, and vibrancy to a younger, wider audience of British people.

The hostile environment

The Windrush scandal began to surface in 2017 after it emerged that hundreds of Commonwealth citizens, many of whom were from the ‘Windrush’ generation, had been wrongly detained, deported and denied legal rights.

Commonwealth citizens were affected by the government’s ‘Hostile Environment’ legislation – a policy announced in 2012 which tasked the NHS, landlords, banks, employers, and many others with enforcing immigration controls. It aimed to make the UK unlivable for undocumented migrants and ultimately push them to leave.

In 2010, the Home Office destroyed the passenger records of the Windrush, meaning it is impossible for some individuals to now prove they are in the UK “legally”. Because many of the Windrush generation arrived on their parents’ passports, the destruction of the landing cards and other records meant that many lacked the documentation to prove their right to remain in the UK.

The Home Office also placed the burden of proof on individuals to prove their residency predated 1973, demanding at least one official document from every year they had lived here. Attempting to find documents from decades ago created a huge, and in many cases, impossible burden on people who had done nothing wrong.

The Oxford University estimates that of around 550,000 people from the Caribbean who migrated to the UK between 1948 and 1973, roughly 50,000 who were still in the UK may not have regularized their residency status.

These individuals became falsely deemed as ‘illegal immigrants’ / ‘undocumented migrants’, and started receiving letters claiming that they had no right to be in the UK. They began to lose their access to employment, housing, healthcare (from the NHS, which had welcomed people from the Caribbean in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s because they did the jobs that others were not willing to do), bank accounts, and driving licenses. Legal citizens were placed in immigration detention, prevented from travelling abroad, and threatened with forcible removal, while others were deported to countries they hadn’t seen since they were children. Those abroad on holiday were refused back into the only country they had ever known.

One highly-publicised case was that of Albert Thompson, who had lived in London for 44 years after having arrived from Jamaica as a teenager. Mr Thompson went for his first radiotherapy session for prostate cancer only to be told that unless he could produce a British passport he would be charged £54,000 for the treatment. Despite having worked as a mechanic and paid taxes for more than three decades, Mr Thompson’s free healthcare was denied and he was evicted, leading him to be homeless for three weeks.

Michael Braithwaite, who arrived in Britain from Barbados in 1961, lost his job as a special needs teaching assistant after his employers ruled that he was an illegal immigrant.

Paulette Wilson had been in Britain for 50 years when she received a letter informing her that she was an illegal immigrant and was going to be removed and sent back to Jamaica. Ms Wilson had left Jamaica when she was 10 years old and not returned since.

I recommend watching Sitting in Limbo, a BBC drama from June 2020 that was inspired by the Windrush scandal and the hostile environment. It’s a really powerful human story that shines a light on the impact of the scandal – you can find it on the BBC iPlayer.

Their unjust treatment provoked widespread condemnation of the government’s failings on the matter, and calls were made for radical reform of the Home Office and the UK’s immigration policy. In response to these demands, then Home Secretary, Sajid Javid announced in May 2018 that the Home Office would commission a ‘Windrush Lessons Learned Review’.

The review, published in March 2020, makes it clear that the Windrush scandal was not an accident, but was the inevitable result of policies designed to make life impossible for those without the right papers. It found that the government ignored repeated warnings, and that ministers were still failing to acknowledge the extent of suffering inflicted on thousands of people who were mistakenly classified as illegal immigrants by the Home Office.

There remains a huge backlog of cases still to be resolved, and the Government compensation scheme has only made a handful of payments. An apology has not yet been made for the way the Home Office has treated the Windrush generation, and the hostile environment policies are still in place.