Project Description

In this week’s UK Black History blog, I’ll be taking a look at the contributions of black soldiers in World War I and World War II.

I recognise that my perspective may have its limitations, so in writing these blogs I’ll be drawing upon reliable sources from the internet, and I’ll include links to articles so that you can read more. If you think I’ve missed something important, or got something wrong, please do comment and let’s open up the conversation to all.

Our schedule is inspired by the suggestions made by colleagues in the recent survey we completed on BHM, and will cover:

- UK black history – from Ancient Britain to the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- UK black history – World War I and World War II

- UK black history – the Windrush generation

- Prominent people in UK black history

It saddens me that the information I’ve been reading in putting this blog together reveals continued racism and inequitable treatment during a time of great Black sacrifice. Whilst I’ve acknowledged this, I hope I’ve managed to focus on and celebrate the enormous contribution that was made.

If you have articles or information you think colleagues will find interesting, please do share them with us by commenting on these blogs.

And finally, if you have Amazon Prime, I recommend checking out ‘Mutiny’, a 50-minute documentary that includes really moving veteran testimonials and tells the story of the British West Indies Regiment in World War One.

World War One

Black soldiers have been a part of British military history since before the formation of a standing Army in the 17th century, and their involvement increased dramatically in the 19th century, including through the Napoleonic Wars and the Boer War. British history books are largely silent about the contributions of Black servicemen in the First World War, and it is often thought that it was a European war, fought exclusively by (white) Europeans. The mainstream media rarely acknowledges the contributions of non-Europeans during the war, and yet there were lots of Black and Asian soldiers. Many men from Britain’s Black communities also joined the war effort, and Black recruits could be found in all branches of the armed forces.

After centuries of slavery, people in the British Caribbean were relishing their freedom, although many were said to take pride in their loyalty to the ‘Mother Country’. For others, playing an active role in the fighting was seen as an opportunity to advance claims for representative government within the islands. When World War One began, West Indians donated large sums of money to aid the war effort, and many men made their way across the Atlantic at their own expense to enlist.

Soon after the war started, soldiers from Nigeria, the Gold Coast, Sierra Leone, the Gambia, and other African colonies were recruited. They helped to defend the borders of their countries which adjoined German territories, and later played an important role in the campaigns to remove the Germans from Africa. Throughout the war, 60,000 Black South African and 120,000 other Africans also served in uniformed Labour Units. By the end of the First World War, most of the British Army in Africa was made up of African soldiers.

Despite their courage and commitment, Black soldiers often suffered racial prejudice, and the War Office rejected several Caribbean volunteers in the early months of the war due to concerns about the number of Black men enlisting – they also threatened to repatriate any West Indians arriving in Britain.

There was a reluctance to deploy West Indian soldiers in frontline positions, especially on the Western Front, based on a racial stereotype that Caribbean men lacked ‘martial spirit’. Instead, they were usually given support roles, performing labour-intensive duties away from the fighting.

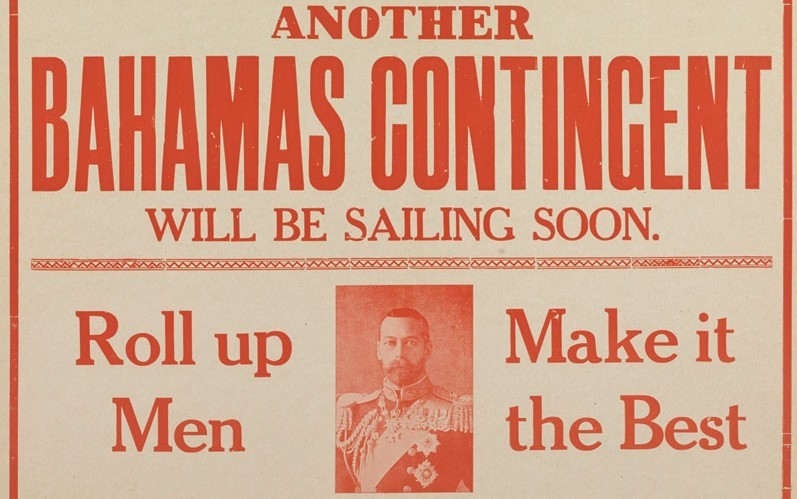

In 1915, following intervention from King George V, a proposal for a separate West Indian contingent to aid the war effort was approved, and the British West Indies Regiment (BWIR) was formed as a separate Black unit within the British Army. The first recruits sailed from Jamaica to Britain and arrived in October 1915 to train at a camp near Seaford on the Sussex coast. The 3rd battalion arrived in early 1916 in Plymouth while other battalions sailed direct to Egypt, arriving in Alexandria in March 1916. In addition to the BWIR, the West Indies contributed men through the West India Regiment (WIR), which had served Britain since 1795.

By the war’s end in November 1918, the BWIR had raised twelve battalions, and around 16,000 Black volunteers enlisted (conscription was never introduced in the West Indies), representing British Guiana and all the Caribbean colonies, with the majority from Jamaica. The Black soldiers of the BWIR received lower pay and allowances than their white compatriots and they were mostly led by white officers and used as non-combatant soldiers in Egypt, Mesopotamia and parts of Europe. The BWIR spent much of their time at labouring work, such as loading ammunition, laying telephone wires and digging trenches, but they were not permitted to fight as a battalion.

Despite the efforts to keep them from combat, the British West Indies Regiment played a significant role in the First World War especially in Palestine and Jordan where they were employed in military operations against the Turkish Army.

In Seaford Cemetery there are more than 300 Commonwealth War Graves and nineteen of the headstones display the crest of the BWIR. The BWIR was awarded 81 medals for bravery and 49 men were mentioned in despatches.

Between the wars

At the end of the First World War, many African and West Indian soldiers who had fought for their ‘Mother Country’ decided to make Britain their home, but in some cities they came under attack. After demobilisation, many ex-servicemen faced unemployment with a surplus of labour and shortage of housing, and returning White soldiers resented the presence of Black men, especially those who had found employment and married White women.

Between January and August 1919, there were anti-Black ‘race riots’ in seven towns and cities in Britain, including Cardiff, Liverpool, South Shields, Glasgow, and London’s East End.

Cardiff’s Black population had increased during the war from 700 in 1914 to 3,000 by April 1919, and the tensions between the White and Black communities exploded into violence in Butetown in June 1919 when 2,000 White people attacked shops and houses associated with Black citizens, and many people were injured. You can read more about the South Wales race riots here.

Liverpool had Britain’s oldest Black community, and by 1919 the number of Black people had risen to 5,000, and there was fierce competition for jobs. Many Black people living in Liverpool had their employment terminated at local oil mills and sugar refineries because White people refused to work alongside them. During Liverpool’s race riots, after a fight broke out in a pub the Police raided boarding houses where Black people lived – Charles Wotten fled, but was chased by a mob into the River Mersey and pelted with stones until he drowned. A plaque was unveiled in his honour in 2017.

While Police bias meant that nearly twice as many Black people as White people were arrested during the race riots, the courts acquitted nearly half of Black arrestees whilst most of the White people were convicted.

World War Two

In spite of racism, Black people from across the British Empire, including Trinidad, Jamaica, Guyana, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone, came forward to help fight the Axis powers during World War Two. Many volunteered to be civilian defence workers, such as firewatchers, air-raid wardens, firemen, stretcher-bearers, first aid workers, and mobile canteen personnel. Additional factory workers, foresters, and nurses were also recruited from across the Empire, including from Africa and the Caribbean, and the efforts of these people were crucial to the home front.

Colour bars (the segregation of people of a different colour or race, especially any barrier to Black people participating in activities with White people and being denied access to the same rights, opportunities, and facilities) had existed in the British Armed Forces before the war, though this was lifted in 1939 as the need to win the war and avoid Nazi victory and occupation outweighed concerns about race and integration. Many Black volunteers from West Africa and the Caribbean were still being rejected by the RAF; however, this changed after the Battle of Britain in 1940. In 1941, 250 Trinidadians were accepted into the RAF and made the journey to Britain, and Black servicemen also went on to help bolster the numbers in the Army and Royal Navy. By the end of the war, in the RAF there were over 17,500 male and female volunteers from the West Indies alone.

Throughout the course of the war, Africa contributed almost one million men to the conflict, across British, French, Italian, and Belgian colonies, as well as those from South Africa. Of that number, some 15,000 British African soldiers were killed over the course of the Second World War. Many Africans who did not fight worked within the African continent to aid the war effort as labourers, porters, carriers, cooks, and mechanics. Thousands of Africans laboured during the war to provide vital food, ammunition, and mineral supplies, without which Britain and the deployed armies would have faltered.

The Second World War led to a substantial increase in the number of Black people living and working in Britain, and existing Black British communities were bolstered by the arrival of war volunteer workers from the Empire, as well as the arrival of 130,000 Black GIs in the US Army’s invasion force. As I’m focusing on UK history, I won’t write about the confrontation and violence that erupted within the US troops based in Lancashire in 1943 as a result of racism and racial segregation, but you can read about the Battle of Bamber Bridge here and here. Interestingly, despite the racial tensions we know of in the UK, the Black US soldiers stationed here saw a great contrast between the non-segregated British society where they were welcomed as fellow fighters against fascism, and the poor treatment they received from the US Army.

Britain’s self-image as a racially tolerant nation had long been shaped by liberalism, and Nazi racial policy made this a particularly salient aspect of national identity during the war – along with a sense of superiority as a result of British society being perceived as more tolerant than that of the US. However, the fight against the evils of racism was at odds with the racial prejudice that clearly still existed, including the colour bar at the start of the war.

Although it seems that slow progress was being made in Britain, when the fighting was over, Britain sent many Black soldiers home with an end-of-war bonus that was roughly a third of the reward given to their White counterparts.

Celebrating Black lives in the World Wars

Walter Tull

Former Tottenham Hotspur player Walter Tull (1888 – 1918) enlisted in December 1914, suffered shell-shock, returned to action in the battle of the Somme, and was decorated with the 1914-15 star and other British war and victory medals. He was commissioned as an officer in 1917 (a significant event as the colour bar in the British armed forces previously prevented anyone who didn’t come from ‘pure European descent’ from becoming officers) and mentioned in despatches for his ‘gallantry and coolness’ at the battle of Piave in Italy in January 1918. Two months later, he was killed in No Man’s Land during the second battle of the Somme.

Robbie Clarke

Robbie Clarke (1895 – 1981) became the first black pilot to fly for Britain, and a pioneer of Britain’s Royal Flying Corps. He was born in Jamaica, and at the outbreak of war in 1914 he travelled to England at his own cost and joined the Royal Flying Corps.

George Roberts

George Roberts (1890 – 1970) was a Trinidadian soldier, firefighter, and community leader in Great Britain. He was known as the ‘coconut bomber’ during the First World War, as he distinguished himself by his ‘extraordinary’ ability to throw bombs back over enemy lines, as he did with coconuts as a child. When the war began, he signed up to the European Service and worked his way from Trinidad to England. He fought in the battles of Loos, the Somme, and in the Dardanelles. After the war, he settled in London where he joined as one of the founder members the League of Coloured Peoples, an influential civil rights organisation. During the Second World War he was too old for combat, so enlisted for the Home Front and became a firefighter during the Blitz. In the King’s 1944 Birthday Honours, he was awarded the British Empire Medal. A blue plaque has been erected in his honour in Camberwell for the first Black man to serve in the army and fire brigade.

Learie Constantine

In 1941, the celebrated Trinidadian cricketer Learie Constantine (1901 – 1971) was employed by the Ministry of Labour and National Service to look after the interests of munitions workers from the West Indies who were employed in English factories. Learie worked tirelessly on behalf of the West Indian war workers. During the war, he continued his cricket career as a league professional, and appeared in many wartime charity games. As a Welfare Officer, he helped the men working in Liverpool factories to adapt to their unfamiliar environment and deal with the severe racism and discrimination which many of them faced, working closely with trade unions. He also used his influence with the Ministry of Labour to pressurise companies that refused to employ West Indians. During the war, at the request of the British government, Constantine made radio broadcasts to the West Indies, reporting on the involvement of West Indians in the war effort. For his wartime work he was appointed an MBE in 1947.

Princess Ademola

Before the NHS was founded in 1948, many West African and West Indian women trained as nurses in British hospitals during World War Two. These included Princess Ademola, daughter of the Alake of Abeokuta, the paramount chief in southwestern Nigeria. She was based at Guy’s Hospital in London.

Adelaide Hall

In 1939, the internationally acclaimed jazz singer Adelaide Hall (1901 – 1993) could have returned home to the safety of New York but she decided to stay in London with her Trinidadian husband and entertain the British public and the troops. She had a special uniform made by Madame Adele of Grosvenor Street. In 1939, she starred in the first live show every broadcasted by the BBC around the globe – a special variety concert recorded at the RAF Hendon base in North London, in front of a specially-invited audience of RAF personnel. She also claimed to be one of the first entertainers to enter Germany before the war had officially ended, travelling with the troops as they advanced towards Berlin.

Ulric Cross

Trinidadian Ulric Cross (1917 – 2013) is often recognised as the most decorated Caribbean airman of World War Two. He joined the RAF aged 24 in 1941, trained as a navigator, and joined 139 Squadron, gaining the nickname ‘The Black Hornet’. He became an expert in precision bombing and joined the ranks of the elite Pathfinder Force, often flying missions at just 50 feet instead of the normal 25,000 feet. After 50 missions, Cross was given the option to rest, he refused and volunteered for a further 30 missions. By the end of the war, Cross had flown 80 missions over Germany and occupied Europe and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in 1944 and the Distinguished Service Order in 1945.

John Jellicoe Blair

John Jellicoe Blair (1919 – 2004) was from Jamaica and joined the RAF in 1941, becoming a navigator in Halifax Bombers flying from Yorkshire. Navigators had to make critical calculations by hand using maps, rulers, and compasses to ensure the aircraft remained on track. He flew 33 operational missions over Europe during the war, despite knowing that if the aircraft went down, his white crewmates would mostly likely to be taken to a prisoner of war camp but as a Black man he would likely be shot on the spot. Blair survived the war and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in 1945. He stayed in the RAF until his retirement in 1965.

Billy Strachan (1921 – 1998) was born in Jamaica, and made his own way to Britain to sign up for the RAF. On his first try he was turned down, but eventually was successful and trained as a wireless operator and air gunner, joining a bomber squadron tasked with making nightly raids over heavily defended German cities. He flew 30 raids over Europe – the average for a bomber crew was around seven. Upon completing his 30th mission, he became entitled to a desk job, but refused this and instead requested to be trained as a bomber pilot. He became known for his daredevil antics, was promoted twice, and ended the war as a Flight Lieutenant.

Lilian Bader (1918 – 2015) was one of a hundred female volunteers from the Caribbean to join the British Armed Forces. She was born in Liverpool to a British mother and Barbadian father, but was orphaned at a young age and raised in a convent. She was dismissed from the Navy, Army, and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI) after her father’s heritage was discovered, but eventually became one of the first black women in the RAF after joining the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) in 1941. She was trained in instrument repair, working on Airspeed Oxford light bombers and was promoted up to the rank of Corporal.

Johnny Smythe

Johnny Smythe (1915 – 1996) was born in Sierra Leone, at that time a British colony, and, unusually for a West African volunteer, successfully made it into the RAF as a navigator. He successfully navigated 26 bombing missions over Germany before being shot down on his 27th mission. He parachuted safety to the ground and was captured, and spent two years in the German Stalag Luft I prison camp before being liberated by the Russians. In 1948, he made history serving as the senior officer aboard the Windrush.