Project Description

It’s just not possible for me to do justice to UK black history in its entirety, so the four blogs on UK Black History that I’ll be sharing during Black History Month (BHM) will focus on particular topics, inspired by the suggestions made by colleagues in the recent survey we completed on BHM. I recognise that my perspective may have its limitations, so in writing these blogs I’ll be drawing upon reliable sources from the internet, and I’ll include links to articles so that you can read more. If you think I’ve missed something important, or got something wrong, please do comment and let’s open up the conversation to all.

In the BHM planning group’s discussions about how we will recognise BHM this year, we talked about the importance of learning and having conversations – and the likelihood that some of this could (and should) cause discomfort. You might find some of the information shared, particularly in today’s blog, upsetting. Some of it was certainly shocking to me, and I hope that many of you will join the discussion in the comments of this blog.

Our schedule will cover:

- UK black history – from Ancient Britain to the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- UK black history – World War I and World War II

- UK black history – the Windrush generation

- Prominent people in UK black history

If you have articles or information you think colleagues will find interesting, please do share them with us by commenting on these blogs. I also recommend watching David Olusoga’s documentary ‘Black and British: A Forgotten History’, which aired on the BBC a couple of years ago – you can still find it on the iPlayer.

UK black history – from Ancient Britain to the Transatlantic Slave Trade, and its enduring legacy

Black people have been living in Britain since at least Roman times. The Roman Empire covered most of western Europe and the Mediterranean, and it was also an African empire, including large tracts of North Africa. Archaeological research indicates that Africans made their homes in the British Isles. We know that African soldiers who served as part of the Roman army were stationed at Hadrian’s Wall during the 2nd century AD.

The “Beachy Head Lady” was a woman from sub-Saharan Africa who was buried in Roman times and is the first black Briton known to us. You can read more here and here about the “ivory bangle lady,” a high-status woman from Roman York whose skeleton was found in 1901. Her remains have been dated to the second half of the 4th century, and she was believed to have been of North African descent. A couple of years ago there was an exhibition at the Museum of London about the diversity of Roman Londinium, which included information about the evidence of people of African ancestry in Southwark.

There are few records of black people in British history until the Tudor period, when there are records of hundreds of migrants living in England. One of the most well-known was John Blanke, an African trumpeter, who is the first black Briton for whom we have a name, and a picture. He can be seen inscribed in a 60-foot-long roll depicting the Westminster Tournament of 1511, an elaborate party which Henry VII put on to celebrate the birth of a son. There is also a letter from John Blanke, successfully petitioning the King for a wage increase.

There is speculation that the woman scholars refer to as “The Dark Lady” in William Shakespeare’s sonnets 127 – 154 was of African descent. It is not known if she was a real person and Shakespeare’s mistress, or if she was a construct of his imagination. She is described as having dark (dun-coloured) skin, and black wiry hair.

Under the influence of European fashion and, later in the 17th century, the expansion of Asian and African trade, more and more black servants began to appear in English households. Waged and enslaved servants formed the largest group of black workers, and having a black servant was often seen as a status symbol. The sale of individual young African men and women was a feature of port city life, particularly in London, and even at the height of the abolitionist movement there were spaces where Africans trained in domestic service could be bought.

By the 18th century, whilst the majority of black people in Britain were employed as servants and we therefore know very little about their lives, there were notable individuals who rose from inauspicious beginnings to comparative fame, including Francis Barber, Olaudah Equiano, and Ignatius Sancho – we’ll write more about them in week four of BHM.

Britain and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Note: The numbers in this section are the recorded estimates, based upon the evidence and records available, and may differ slightly depending on the source – however, it is believed that there are many more lives unaccounted for.

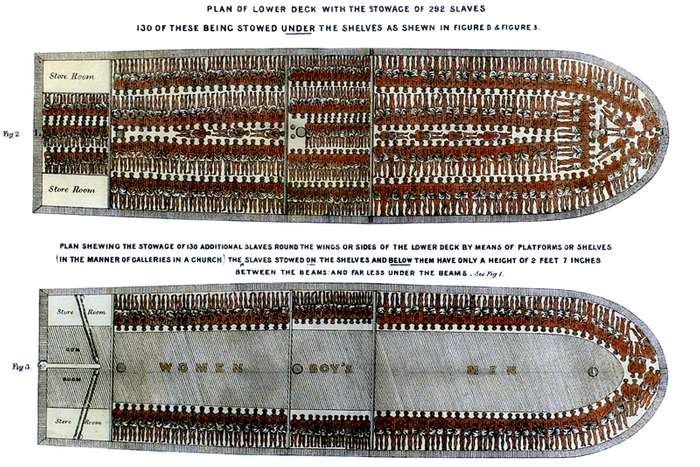

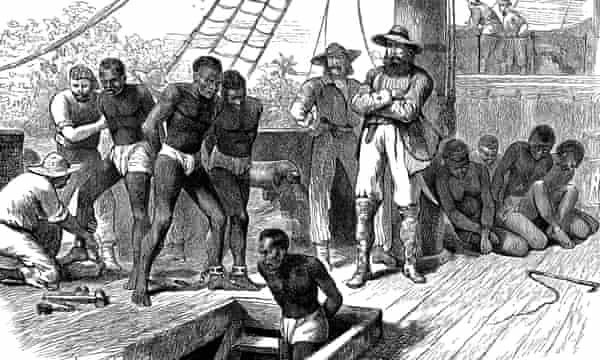

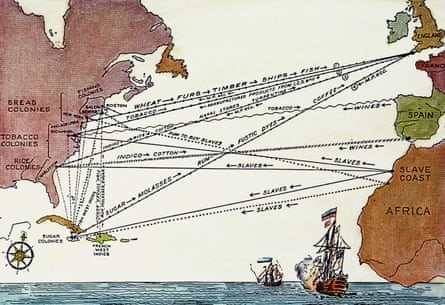

The Transatlantic trade of enslaved Africans was a triangular route from Europe to Africa, to the Americas, and back to Europe. On the first leg, merchants exported goods to Africa in return for enslaved Africans, gold, ivory, and spices. The ships then travelled across the Atlantic to the American colonies where the Africans were sold as slaves to work on plantations and as domestics. The goods exchanged (sugar, tobacco, cotton, and other produce) were transported to Europe.

John Hawkins is considered to be the first English slave trader. He captured over 1,200 Africans and sold them as goods in the Spanish colonies in the Americas. He left England in 1562 on the first of three slaving voyages, and in 1563 he sold slaves in St Domingo. In the 245 years between Hawkins’ first voyage and the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, merchants in Britain despatched about 10,000 voyages to Africa for slaves, with merchants in other parts of the British Empire carrying out around a further 1,150 voyages. Only the Portuguese, who carried on the trade for almost 50 years after Britain had abolished its slave trade, carried more enslaved Africans to the Americas than the British.

In the 1640s, Dutch merchants introduced sugar to Barbados, and showed planters there how to grow and process sugarcane. Sugar was an important commodity, and Barbados (which became a British colony in 1625) rapidly converted from many small farms growing crops, cotton, and tobacco, to a few wealthy landowners who grew sugarcane on large swathes of land. The Dutch supplied Barbadian planters with Africans, and convicts and indentured servants from Britain were also employed. Sugarcane required large numbers of labourers, so laws were soon passed to restrict the rights of slaves by classifying them as property, and the number of African slaves on the island increased.

In the 1660s, the number of slaves taken from Africa in British ships averaged 6,700 per year. By the 1760s, Britain was the foremost European country engaged in the slave trade. Of the 80,000 Africans chained and shackled and transported across to the Americas each year, 42,000 were carried by British slave ships. Between 1750 and 1780, about 70% of the government’s total income came from taxes on goods from its colonies.

Britain was one of the most ‘successful’ slave-trading countries. Together with Portugal, the two countries accounted for about 70% of all Africans transported to the Americas. Britain was the most dominant between 1640 and 1807, and it is estimated that Britain transported over 3.1 million Africans (of whom an estimated 2.7 million arrived – captives were often thrown overboard when they were too sick, or too strong-willed, or too numerous to feed) to the British colonies in the Caribbean, North and South America and to other countries. The early African companies developed English trade routes in the 16th and 17th centuries, but it was not until the opening-up of Africa and the slave trade to all English merchants in 1698 that Britain began to become dominant. The slave trade was carried out from many British ports, but the three most important ports were London (1660-1720s), Bristol (1720s-1740s) and Liverpool (1740s-1807), which became extremely wealthy. Under the 1799 Slave Trade Act, the slave trade was restricted to these three ports.

By the end of the 18th century, Britain was the leading trader in human lives across the Atlantic. There were over a million enslaved Africans in the British West Indies. Working a minimum of 3,000 unpaid hours yearly, they generated much of the wealth from which the new British manufacturing economy would be created. Inevitably, black people had been arriving in all parts of the British Isles, unwillingly and willingly, for over two centuries. Current estimates are that at least 10,000 lived in London, with a further 5,000 throughout the country.

By the end of the 18th century, the British Army was the largest single purchaser of enslaved Africans in the Caribbean. A total of 6,376 people were bought for immediate military service in the area from 1798 to 1806.

During the American Revolutionary War Africans fleeing captivity were offered their freedom should they join the British armed forces. With the collapse of the British campaigns in North America, several thousand black troops (some with their families) fled to British-held territories. Over one thousand made their way to Dublin, Liverpool, and London.

Black soldiers were also recruited from those born in the British Isles and were found in the ranks of ‘county’ regiments and foot guards.

Britain could not have become the most powerful economic force on Earth by the turn of the 19th century without commanding the largest slave plantation economies in the world, with more than 800,000 people enslaved. The profits of slavery have an enduring legacy today, and helped finance the Industrial Revolution, built mansions, established banks such as the Bank of England, and funded new industries. The profits were felt throughout Britain, including factory owners making textiles that were bought by slave-captains to barter with, the building of industrial plants to refine the imported raw sugar, the making of glassware to bottle the rum, banks and finance houses growing rich from the fees and interest they earned from merchants who borrowed money for their long voyages, and the growth of ports such as Bristol and Liverpool through fitting out slave ships and handling the cargo they brought back. The slave trade also provided many jobs for British people – including in factories which sold their goods to West Africa, which would be traded for enslaved Africans, and gun-makers in Birmingham with 100,000 guns a year being sold to slave traders.

The legacy of such large-scale, prolonged slavery also lives on in and is imprinted in Britain today, through buildings named after slave owners, such as Colston Hall in Bristol (which featured in news reports as a result of Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020 and was renamed ‘Bristol Beacon’ in September), streets named after slave owners such as Buchanan and Dunlop Streets in Glasgow, and whole parts of cities built for slave-owners, such as the West India Docks in London – not to mention British tastes such as sweetened tea (sugar being made more affordable for people living in Britain as a result of slave labour), silver service, and cotton cloth-work, and continuing race and class inequalities.

Abolition of the British slave trade

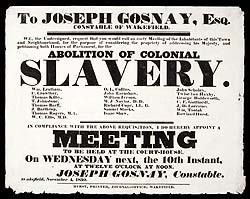

In 1783, an anti-slavery movement to abolish the slave trade throughout the British Empire had begun amongst the British public.

The Crown had allowed American Loyalists fleeing the United States after the American Revolutionary War to bring slaves to Canada by the Imperial Act of 1790. The slave Chloe Cooley was brought to Canada by an American Loyalist, and when he feared he may be forced to free her, he arranged a sale, against her will, to an American across the Niagara. In order to make the sale, he beat Cooley, tied her up, and forced her into a small boat. Charges were brought against him for disturbing the peace, which were dropped because Cooley was considered property. This acted as a catalyst, as Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe was outraged by the incident. Canada passed the first legislation to outlaw the slave trade in a part of the British Empire, after Simcoe tabled the Act Against Slavery in 1793.

Anti-slavery campaigners lobbied for twenty years to end the trade, and the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed in Britain in 1807. The Act outlawed the international slave trade, but did not abolish the practice of slavery. The legislation was timed to coincide with the expected prohibition from 1808 of international slave trading by the United States, Britain’s chief rival in maritime commerce. Whilst the legislation created fines for captains who continued with the trade, this did little to deter slave trade participants, and trading continued. Further legislation followed, including the Slave Trade Felony Act 1811 which made overseas slave trade a felony throughout the British Empire.

The Royal Navy established the West Africa Squadron to suppress the Atlantic slave trade by patrolling the coast of West Africa. It did suppress the slave trade, but did not stop it entirely. Captains would sometimes dump captives overboard when they saw Royal Navy ships coming, to avoid fines of up to £100 per enslaved person found on a ship. Between 1808 and 1860, the West Africa Squadron captured 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans, resettling many in Jamaica and the Bahamas. The passing of these Acts also encouraged British action to press other nations to abolish their own slave trades – this created treaties that allowed the Royal Navy to seize other countries’ slave ships.

Whilst the slave trade had been abolished, slavery itself remained very profitable and sugar plantations in the Caribbean, where slavery thrived, were lucrative. From 1823, the British Caribbean sugar industry went into decline, and the British parliament no longer felt it needed to protect the economic interests of the West Indian sugar planters.

In 1823, the Anti-Slavery Society was founded in London. Members included Joseph Sturge, Thomas Clarkson, and William Wilberforce. Jamaican mixed-race campaigners such as Louis Celeste Lecesne and Richard Hill were also members. Its work included supporting the first slave narrative to be published by a black woman, Mary Prince, ‘The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave’ in 1831.

Sugar plantation owners from rich British islands such as Jamaica and Barbados were able to buy ‘rotten and pocket boroughs’ (parliamentary boroughs or constituencies that had a very small electorate), to gain unrepresentative influence within the unreformed House of Commons. This enabled the West India interest (around 80 MPs along with an additional group of around 10 MPs who did not own slaves themselves, but still opposed any proposal to tamper with slave owners’ right to ‘property’) to form a body of resistance to moves to abolish slavery itself. The Representation of the People Act 1832 (the Reform Act) introduced major changes to the electoral system, and swept away these seats.

This cleared the way for the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, which abolished slavery itself in parts of the British Empire, making the purchase or ownership of slaves illegal within the British Empire, with the exception of the ‘Territories in the Possession of the East India Company’, including Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and Saint Helena (which the Company had been independently regulating and in part prohibiting the slave trade since 1774 – the Indian Slavery Act 1843 went on to prohibit Company employees from owning or dealing in slaves).

However, despite the 1833 Act, for many of those enslaved, slavery continued until at least 1838 through ‘apprenticeship’ schemes which involved continued unpaid labour on plantations. A state-funded corps of police, jailers, and enforcers was hired in Britain and sent to the plantation colonies to enforce labour standards and issue punishments. It is also believed that after 1833, clandestine slave-trading continued within the British Empire. Modern slavery, both in the form of human trafficking and people imprisoned for forced or compulsory labour, continues to this day.

The passing of the Act and the emancipation of enslaved Africans became possible by treating them as property, rather than as people. Abolition meant that wealthy slave owners would no longer be able to profit from the African slaves in their possession. The Slavery Abolition Act provided for payments to slave owners, to compensate for the loss of their property when the slaves were freed. Under the Act, the British government paid £20 million to the registered owners of freed slaves – this was 40% of the Treasury’s annual income, or 5% of British GDP at the time. In today’s money, that figure equates to around £16.5 billion. It was financed by a £15 million bank loan, and £5 million was paid out directly in government stock, worth £1.5 billion in the present day. Half of the money went to slave-owning families in the Caribbean and Africa, while the other half went to absentee owners living in Britain.

More than 50% of the total compensation went to just 6% of the total number of claimants, with the benefits of slave-owner compensation being passed down from generation to generation to the current day. The enslaved receiving nothing to redress the injustices they suffered, and the British state has never apologised or paid any reparations to the people it enslaved or their descendants.

The money was not paid back by the British taxpayers until 2015, when the British Government decided to modernise the gilt portfolio by redeeming all remaining undated gilts. Shockingly, this means that most of us have, in our lifetimes, contributed to the compensation of British slave owners.

Some articles for further reading:

- There are British businesses built on slavery. This is how we make amends – Catherine Hall, The Guardian, 23 June 2020

- How Britain is facing up to its hidden slavery history – Holly Williams, BBC Culture, 3 July 2020

- Britain’s Slave Trade Story Isn’t History – It Still Resonates Today – Charlie Duffield, 23 August 2018